It’s a lovely morning in the village, and you’re a horrible goose.

That is, in a nutshell, the premise of Untitled Goose Game, a “slapstick-stealth-sandbox” puzzle game released by House House in 2019. The player assumes the role of a goose, who uses its limited physical abilities and the manipulation of objects within its world to unlock achievements—all of which involve pestering unsuspecting townspeople.

Le honk.

While the gameplay is relatively straightforward, Untitled Goose Game’s dynamic soundtrack offers an interesting take on music and mood. Rather than composing an original soundtrack, the game developers borrowed selections from Claude Debussy’s Préludes (which are now in the public domain). Elements of urgency, surprise, movement, and mischief are infused into the existing music by altering its tempo, pulse, volume, and register. Composer Dan Golding describes the creative process in an interview with Paul Dougherty of Zoneout:

There are two performances of every Prélude on the soundtrack – one version that is similar to how you’d typically hear the music performed, and another which is slower and has lower energy. Both of these performances are chopped up into about 300 to 400 short fragments, each between one and three seconds long, that are queued to trigger in order.

The game then chooses which of the two versions to trigger depending on what the player is doing. And if the player is doing nothing, the soundtrack remains silent.

The game is comprised of five settings within an English village, each featuring a Prélude: The Garden (Minstrels*), High Street (Les Collines de Anacapri), the Back Gardens (Hommage à S. Pickwick, Esq. P. P. M. P. C.), The Pub (Le serenade interrompue), and the Model Village (Feux d’Artifice).

The differences between the original Préludes and their modified versions are most pronounced upon entering each world, when the goings on in the game are still relatively low-energy. Minstrels, for example, has a sense of ambiguity achieved by exaggerating Debussy’s instructions to hold back (cédez, which translates literally as “give up”) after each four-bar phrase. Golding expands upon this by hesitating between each 5-1 movement in the bass line (Example 1), momentarily denying our ears resolution.

Example 1 Minstrels

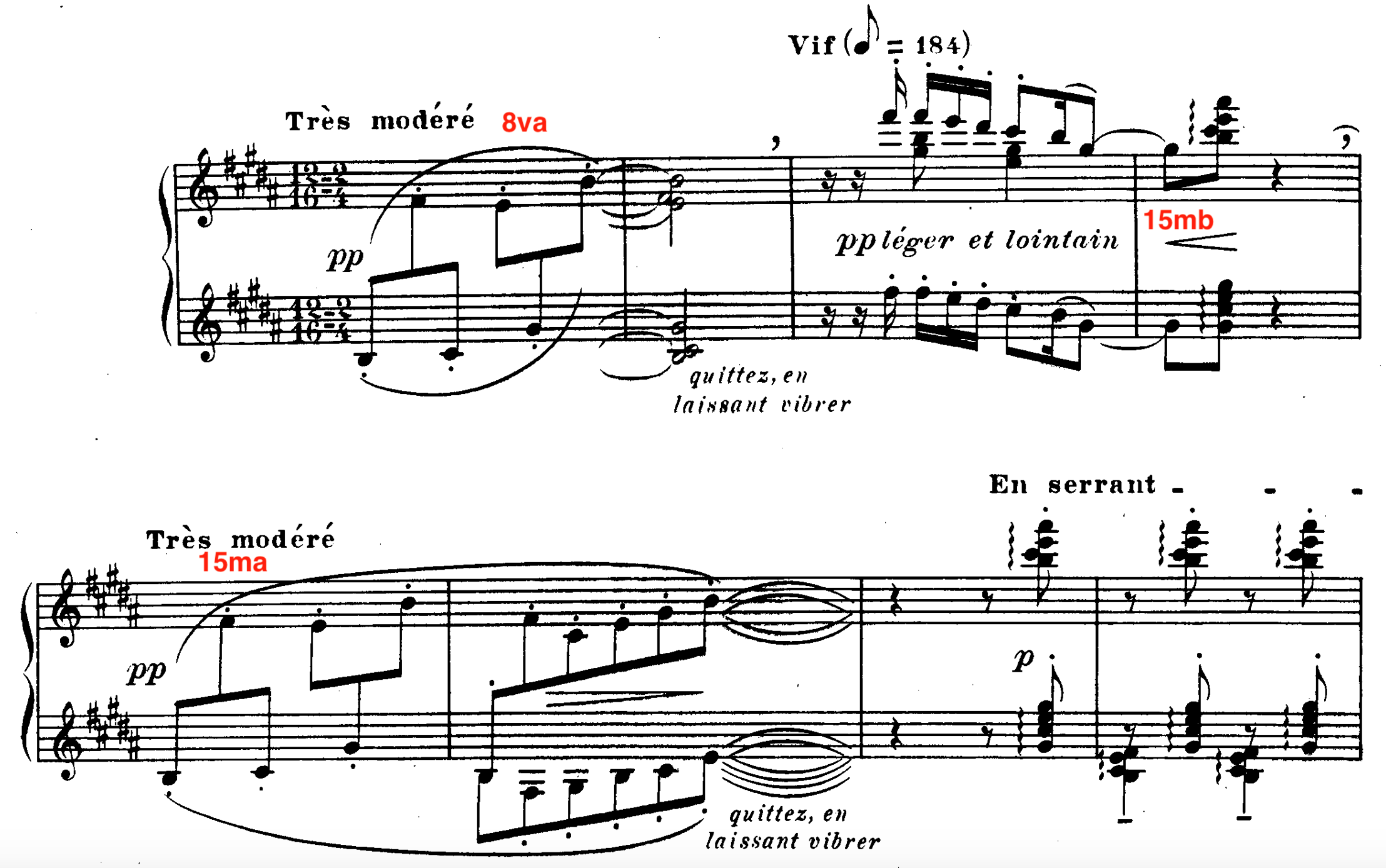

Similarly, when comparing the standard Les collines d’Anacapri to its in-game counterpart, the most obvious adaptation is the tempo, which Golding has dramatically reduced. The register has been altered, too. The opening figures have been raised an octave in some instances and lowered by an octave in others. The cumulative result is a contemplative mood reflective of a sleepy village yet to endure the goose’s undoing.

Example 2 Les collines d’Anacapri: changes made to register in Golding’s low-energy interpretation are marked in red.

The phrasing in Golding’s low-energy interpretation is, in places, nearly inverse of the original. The first climax (m. 21) is treated as more of an afterthought than a point of arrival, trailing away in both pulse and volume (not unlike a distracted goose). The dotted-sixteenth thirty-second motive (seen in m. 17 and throughout the piece), on the other hand, is voiced more emphatically than is typical, lending a sense of playful clumsiness (also not unlike a distracted goose).

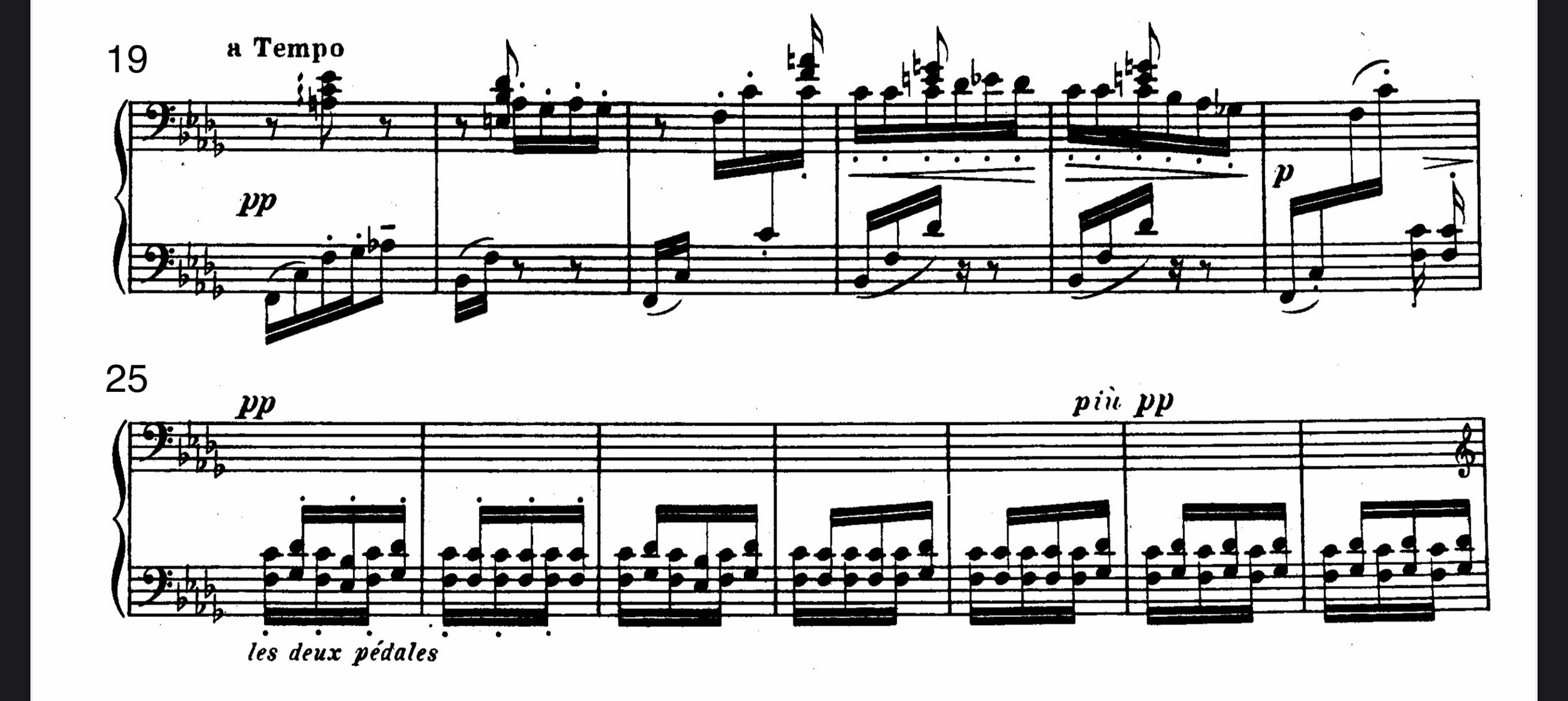

Example 3 Hommage à S. Pickwick, Esq. P. P. M. P. C.: m. 17 shows the dotted-sixteenth thirty-second note motive that recurs throughout the piece; Debussy’s instructions for the climax in m. 21.

Le serenade interrompue: A Deep Dive

Le serenade interrompue, aside from a relaxed tempo, remains relatively unchanged until measure 62, when a caesura is added before a syncopated melody begins. Meant to imitate a Spanish guitar—Debussy’s instructions state quasi guitarra, or “like a guitar”—the texture and articulation suggest strumming (mm. 21-23) and plucking (the ostinato beginning in m. 25). However, when performed under tempo with a heavier articulation, the ostinato becomes bumbling and pervasive (again, not unlike a distracted goose).

Example 4 Le serenade interrompue, with a strummed texture in the first system and a plucked texture in the next system.

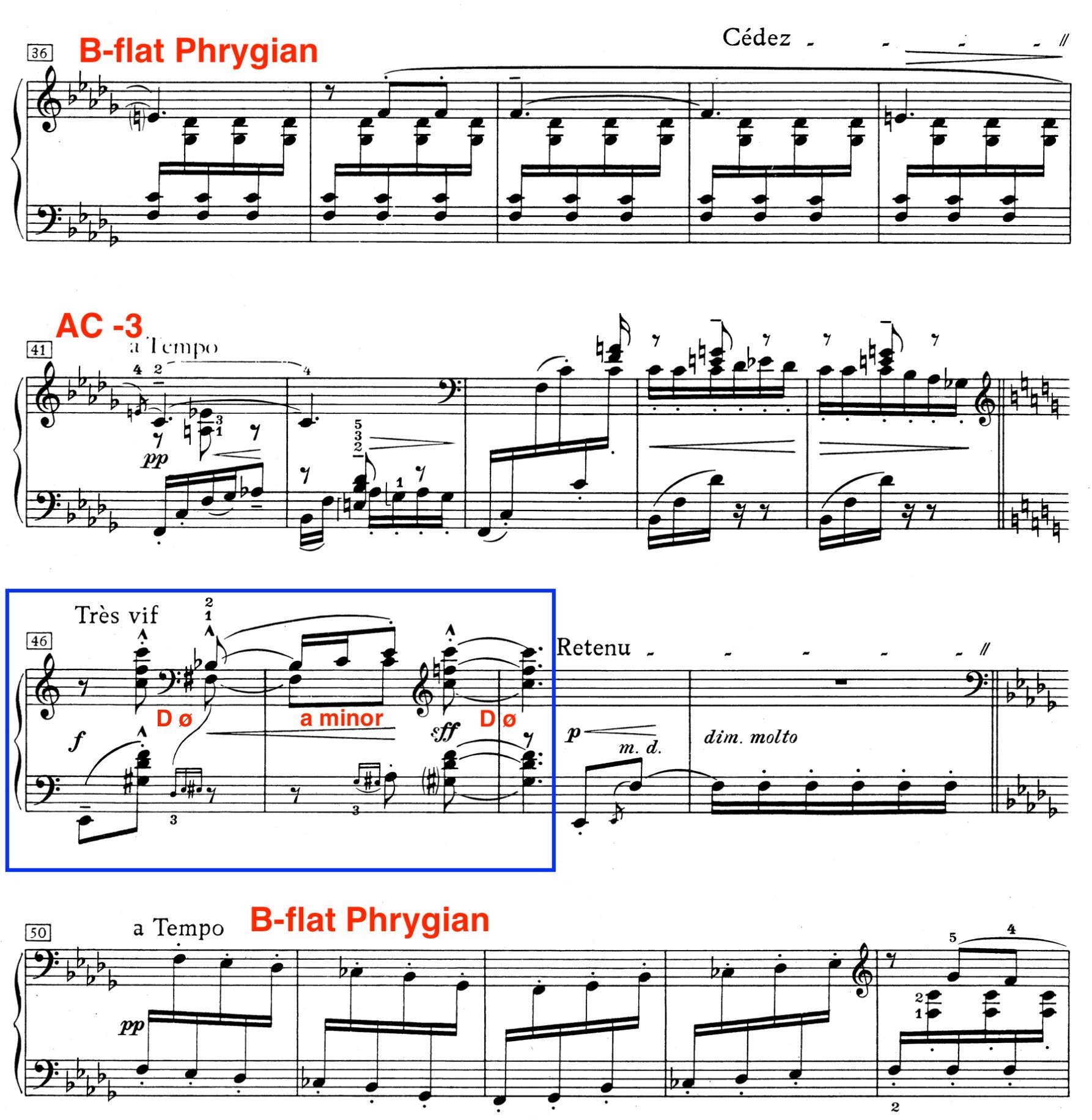

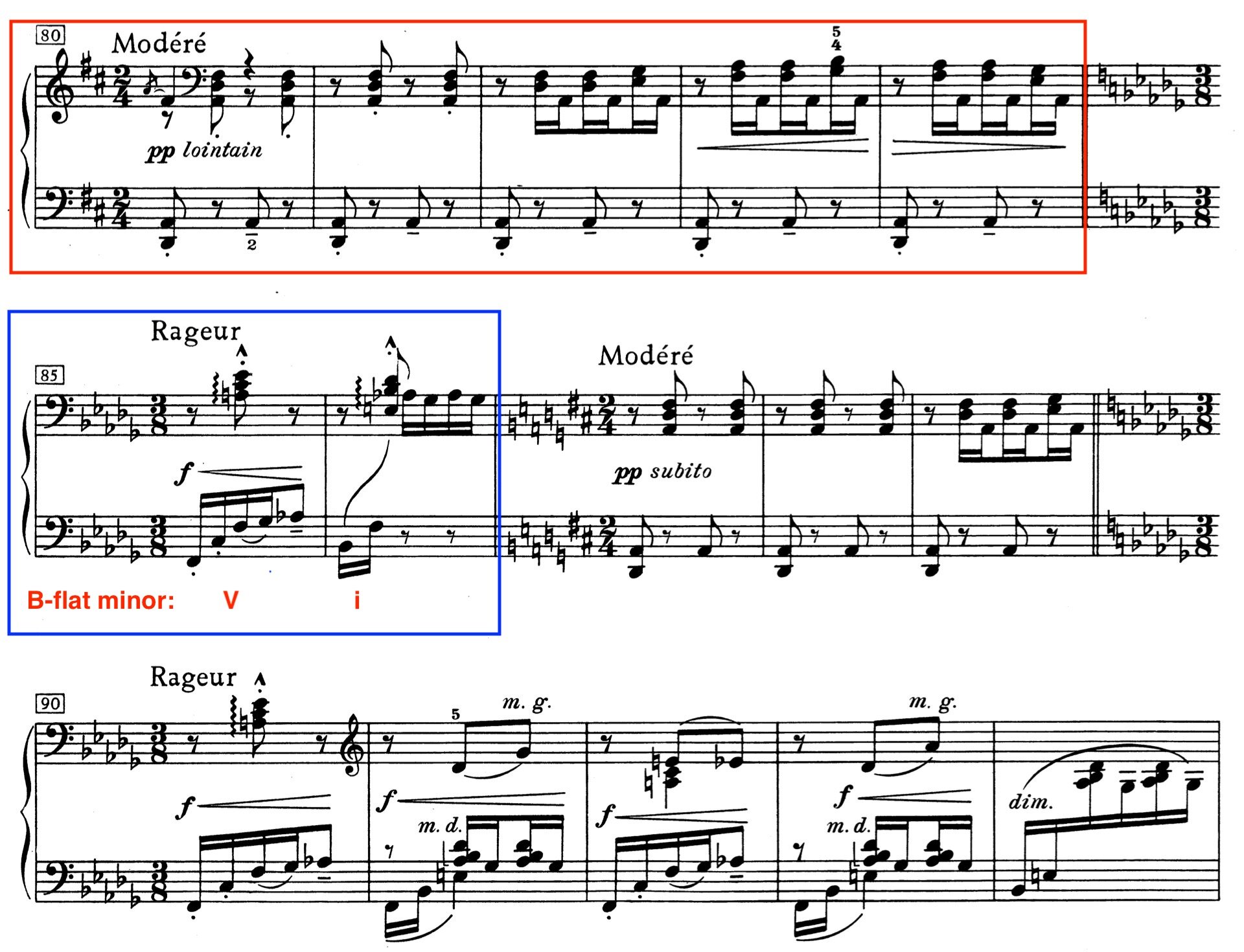

This Prélude is perhaps the most overtly programmatic of those used in the game’s soundtrack. It tells the story of one lover serenading another—but with interruptions that come not only through abrupt, brief changes in harmony and dynamics (mm. 46-49), but also through prolonged changes in style (mm. 80-84, and again in mm. 87-89). The longer “interruption” passages sound like background music within the musical world: yet another thing with which the guitarist must compete. In the context of the game, another layer of storytelling is added through the interrupting goose. Even without modifications, Le serenade interrompue tells a story.

Example 5 Le serenade interrompue: The harmony changes abruptly from an acoustic collection (-3) to unrelated half-diminished chords, which might be interpreted a few different ways (that is beyond the scope of this blog post). Nonetheless, measures 46-47 are a clear interruption—not only through harmony, but also through volume and texture.

Example 6 Le serenade interrompue: Measures 80-84, clearly in D major, feature a march-like style not seen in any other section of the piece—the guitarist is competing with other music within his world. His sentiment toward this more prolonged interruption shows in mm. 85-86, marked Rageur (furious). Golding’s interpretation places this interruption two octaves higher.

While exploring the individual alterations to each piece is interesting, it’s the instantaneous change in affect enabled by the juxtaposition of the altered and original versions that make the magic of the soundtrack. The player never hears the same combination of versions twice during gameplay.

Though Debussy’s Préludes seem to have been chosen for the soundtrack by chance, the way Debussy handles titling the compositions makes them a striking fit for a reactive soundtrack. Although Debussy gives interpretive instructions on the score—sometimes using standard musical terminology, but sometimes using descriptive phrases unique to a particular Prélude—no title is revealed until the end of the piece. This allows the listener to subjectively submerse themselves in the melodic, harmonic, textural, and even timbral elements that Debussy combines to create a soundscape. What we ultimately find to be titled Le serenade interrompue (“The Interrupted Serenade”) may have evoked different images for different listeners.

What does a terrible goose have to do with piano pedagogy?

I have always found movie and video game soundtracks to be of pedagogical value, especially if they are already of particular interest to students. What can we learn from reactive soundtracks? These are some thoughts that came to mind as I compared the Untitled Goose Game soundtrack to standard performances of the Préludes:

What effect does register, specifically, have on mood? Could students create a sense of atmosphere using only one pitch in different registers? This might be a great starting point for students who are overwhelmed by improvising.

What elements do composers manipulate to create different moods?

How would the mood of a piece change if we played certain elements—dynamics, articulations, tempo markings—oppositely? Taking a trip to what my young students and I call “Opposite Land” can also be a good way to make students more sensitive to a piece’s intended markings.

How do we know what a piece could be about without using the title as an influence?

It’s worth noting that we can give any piece the “Debussy treatment” by covering its title and having students imagine what the piece might be about—then compare their title to the original one. We can also turn any piece into the soundtrack to a story we create ourselves. Sonata-Allegro form, with themes of contrasting affect in the exposition and harmonic exploration in the development, lends itself especially well to storytelling. In smaller-scale teaching pieces like sonatinas (or other forms that don’t typically have imaginative titles) we might:

Associate dynamic levels or major/minor sonorities with a particular character.

Imagine different characters for the right and left hands.

Use formal sections to guide the story.

Storytelling through music is a topic of its own, but I found it impossible to discuss a reactive soundtrack (music to fit an ever-changing story) without at least touching upon the pedagogical tool of narrative (creating a story to fit music).

Although the soundtrack to Untitled Goose Game happens to be classical, I hope that this blog post provokes some thought about the value of video game music—in the Western classical tradition or otherwise—and its potential as a creative tool.

* Debussy’s Minstrels alludes to minstrelsy (defined by Oxford Languages as the form of entertainment associated with minstrel shows, featuring songs, dances, and formulaic comic routines based on stereotyped depictions of Black Americans and typically performed by white actors with blackened faces). This is no doubt problematic, and it’s necessary to discuss how to handle repertoire like this. An obvious option is to boil the piece down to its technical components and select a different piece with similar pedagogical concepts. Another option for Debussy’s music, specifically, is to give the student power over the piece by having them listen to it and create their own title. Since Debussy placed the title of each Prélude at the end, taking such liberty is not only appropriate, but encouraged. I usually choose the former.